Selling a Private Company; When and Why to Consider Using an Investment Banker Instead of a Business Broker

Dec 09, 2022Selling a Private Company; When and Why to Consider Using an Investment Banker Instead of a Business Broker

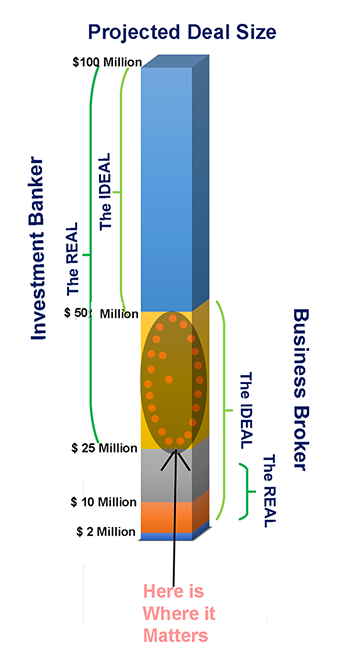

The differences between a business broker and an investment banker mainly matter to private companies big enough to be of interest to an investment banker but not out of scale for a business broker, say those in the $25-$50 million revenue range. Choosing one or the other is not about deal size in and of itself; the correlates of deal size drive the choice. Bigger privately-held companies attract buyer prospect interest from a wider array of buyer entity types, national or international in scope. They tend to have more constituent stakeholders to satisfy and to receive more complexly structured offers. As the buyer prospect list by type and geography and your stakeholder constituencies diversify, and the menu of means for resolving all of the interests of buyer and seller become richer in available choice, you will find it appropriate to think about talking to investment bankers. This post dissects the differences, regulatory origins, and practical consequences distinguishing business brokers and investment bankers so you can evaluate which professional is likely to be a better choice for you to realize maximum recoverable equity value in the sale of your business.

I'm Michael Kane. I've been an investment banker for 32 years. I strategize, structure, negotiate and close the sale of your company, mergers, acquisitions, and IPOs. I advise Boards evaluating strategic alternatives. I restructure liabilities if things aren't going well. I collaborate with company owners, controlling shareholders, senior management, board directors, private equity staff, top-flight lawyers, and accountants. If you are accountable for a strategic financial transaction, I teach you how to improve the value significantly you deliver to shareholders. You can engage our firm to lead your transaction or, on a more limited basis, coach you through difficult issues. You can select video courses from our growing list if you want a practical orientation to how various deal types work. I'm also doing a series of blog posts on things I've seen happen, some funny, some not so much. Occasionally I'll contribute a dose of reality to clarify the oversimplifications and sound bites the falsely confident make about how things work in the M&A world. That's what I'm doing here. As I am the active Managing Partner of an SEC/FINRA/SIPC-registered private investment bank, neither a journalist nor pundit nor gadfly nor retired, if you haven't already, please read the first post published in this series to understand the regulatory standards under which I publish.

The Truth Beyond the Sound Bite. When I started this post to explain when prominent private companies should, instead of a business broker, consider hiring an investment banker to quarterback the sale of the company, I thought writing would be easy. I would tote up the conventional wisdom about when to hire a broker or a banker. Little deal = business broker. Big deal = investment banker. I discovered it was a mistake to accept the sound bite comparisons frequently shot from the hip and skewed by whether the person giving them was a broker or a banker or whose referral source or friend was one or the other. When I put myself in the position of the business owner trying to make a choice, it was not so simple. I learned that business brokers are more constrained than I've ever heard one admit about when they can serve a client for compensation on any size sale transaction. However, if the sale process stays in the middle of the fairway carved by the regulatory exemption that permits them to exist, then there is no upper limit to the size deal a business broker can facilitate. Assuming the client company is privately held, what matters is whether the buyer prospect pool will likely include entities to which a business broker cannot sell, by deal structures a business broker may not facilitate, requiring assistive techniques federal regulators prohibit business brokers from providing. The kernel of truth is that as the projected deal size increases, the buyer pool increases, and deal pathways and structures emerge that a business broker cannot serve. There is a reciprocal side to this as well. The investment bankers are trained, have taken the required substantive competency tests, are supervised by their firms, and are continually surveilled by regulators to ensure that they are qualified to function well in the more challenging and potentially more rewarding deal environment to which your prominence and projected deal size grant entry.

You Get What You Bargain For. Which professional can do what is governed by a tradeoff, basically two different bargains with the federal regulators. Investment bankers and their firms accept and live with comprehensive, expensive regulation, oversight, auditing, enforcement, and compliance performance tracking transparent to the public. In exchange, investment bankers' permitted scope of service includes anything legally necessary to get your sale consummated to your satisfaction in any deal space. Business brokers, quite reasonably, did not want the burden and expense of federal regulation to work with privately-held companies. To accommodate this, federal regulators and Congress established an exemption from regulation for business brokers serving smaller privately-held companies, accompanied by strict conditions on the permitted scope of service. The limitations on business brokers will tend to cut off their ability to serve privately-held companies as the buyer prospect pool increases in volume, type, and geographical dispersion; the number and type of stakeholders grow, and the complexity of the deal required to resolve all of the interests deepens.

First, the basic rules. Federal regulators permit business Brokers to facilitate the transfer of ownership and control of privately held companies (only) for compensation under an exemption from registration with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Association (FINRA). Any exchange of securities in the deal must also qualify for an exemption from registration under the Securities Act of 1933. To be eligible for the federal exemption, a business broker cannot arrange to finance a transaction, form a group to buy a company, sell to a passive buyer (the buyer must control and actively operate the company after the close), or come into possession of the funds for the purchase at any stage of the sale process. Those states, such as California, that also permit an exemption from registration for business brokers under state securities laws require a real estate brokers license. There are no provisions for hybrids, say, a business broker claiming to distribute any non-exempt securities in a deal through an "arrangement" with a registered broker-dealer. Either the securities broker-dealer registers and directly and accountably supervises all of the activities of the professionals (which would make them investment bankers), or they don't, which means the business broker would be violating the conditions on the federal exemption that allows them to exist. Violations at the federal and state level trigger the disgorgement of fees, citations, and fines in actions brought by regulators and can lead to further civil liability to parties of a transaction.

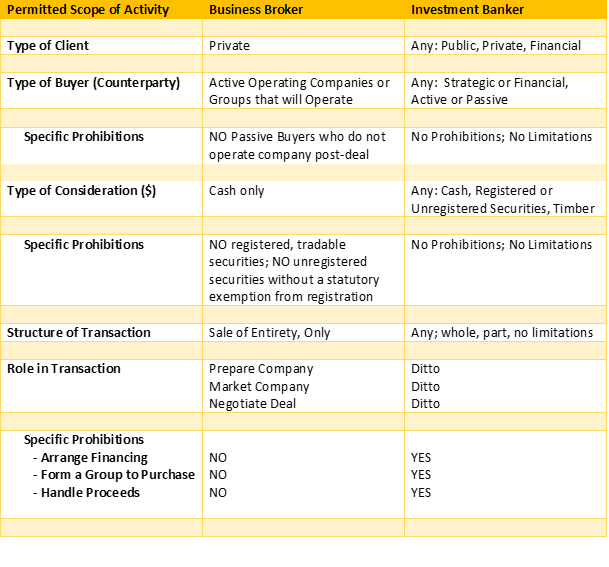

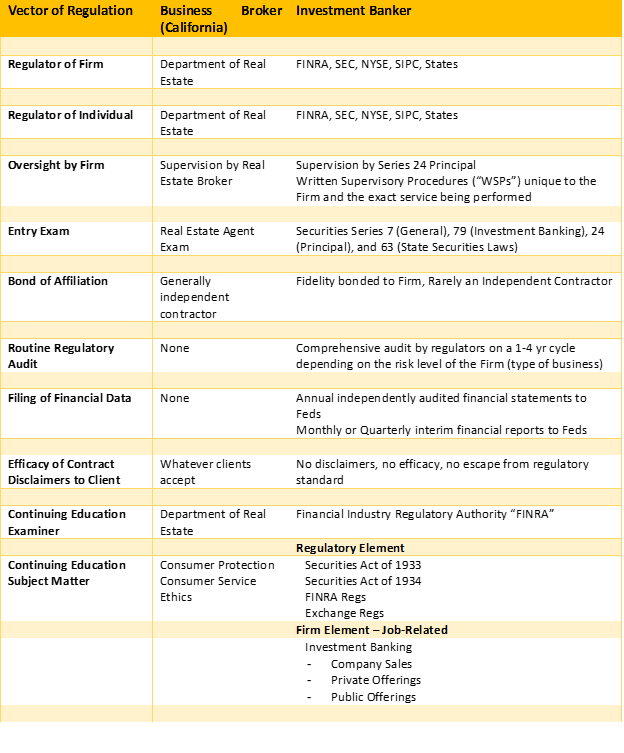

Investment bankers and their firms are registered and heavily regulated. They have none of these restrictions. The table immediately below summarizes each type of professional's permitted scope of activity. This post concludes with a table summarizing a comparison of regulatory requirements, standards, and burdens (or lack thereof) that justify the permitted scope of activity differences.

Generally, how does the market shake out between business brokers and investment bankers?

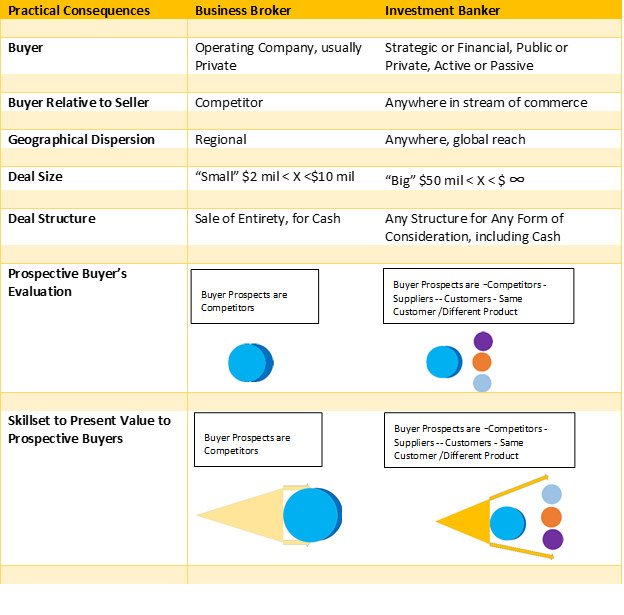

Business Brokers generally do deals between $2 and 10 million ($5 million to $50 million is a commonly advertised aspirational range). Investment bankers' deals typically exceed $50 million, but they will assist with smaller deals in certain circumstances. If an investment banker does a smaller deal, the regulatory burden on the banker and firm does not decrease with the deal size. Private companies, closely held, tend to have fewer than five shareholders, which is the typical purview of the business broker. Investment bankers work with private and public companies from one to thousands of shareholders. Business brokers sell businesses to other private companies or the portfolio companies of financial buyers (not the financial buyers themselves, as this would violate the "no passive buyers" condition for the exemption, and the buyers must operate the company post-transaction), generally in the same region as their client company. Investment bankers sell to private and public companies and financial buyers anywhere in the world. A business broker most often does deals for cash, sometimes cash with an earnout in cash, and more rarely for unregistered securities exempt from registration under the Securities Act of 1933. Investment bankers will sell a company for whatever their client seller wants to accept, including cash or various types of securities, registered or unregistered, or payment-in-kind. Business brokers structure their deals as sales of the entirety. Investment bankers will sell the client company, sliced and diced (or not), any way the principals want to do the deal.

Company-Centric Orientation to Value. Because each type of professional plays on a different game board, they will evolve different orientations to valuing a client company to be sold. The business broker will most often sell to another operating company, and the deal is on the smaller side, likely to a buyer in the same region as the client. The buyers will tend to be competitors, either directly or indirectly. That means many buyer prospects value the selling company using the same evaluation criteria they use to measure their own business and value. The business broker assesses their client company's value compared to any well-run business and then comparatively relative to its direct peers and industry average benchmarks. To realize greater value, the client company will repair any divots and improve itself to meet or exceed the benchmark values established within its industry among competitors.

Market-Centric Orientation to Value. As beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and investment bankers typically work with a more comprehensive array of beholders, the perception of the client's value becomes more complex. Like the business broker, the investment banker will measure the client on metrics concerning any well-run company, direct peers, and industry benchmarks. And then it gets more interesting. Frequently the buyer prospect pool includes, in addition to competitors, other companies in the stream of commerce relative to the client business, such as customers, suppliers, and further afield, companies that serve the same customers but with complementary or completely different products and services (think Beats™ and Apple™). The prospect pool also includes financial buyers, who may be unavailable to a business broker because the purchasing entity may not "operate" the company post-transaction. I have observed that among strategic buyers, competitors pay the least for peers because they value only what the target company brings at the margin of the business the competitor already has. Financial buyers, on average, pay the least because they evaluate a target as would a competitor and then step on the purchase price as the only method of mitigating the risk of not already being in the business. Other companies in the stream of commerce, relative to the client, can pay more because the client brings more of what the prospective buyer does not already have. In other words, familiarity breeds contempt, and dissimilarity generates excitement about the possibilities of sales and product synergies, not just cost savings. That is where purchase price multiples develop room to run.

Different Methods of Expressing and Selling Value. The difference in orientation to value based on the different fields of play between brokers and bankers leads to a different set of skills for expressing the value of a client to the buyer prospect pool. For the client of the investment banker, a wider field of play among the prospective buyer pool opens the door to imagination and creativity to inspire salesmanship. It's not just about what the client company is; it's also about what given companies in the buyer prospect pool can do with the client company. Different classes of buyer prospects value the client differently, based primarily on what the client company brings to THEM, what they specifically can do with the client, and how they uniquely can economically exploit the client. To some classes of buyers, the value they see is not incremental, as the competitor sees it; it's factorial. It's the bankers' job to figure that out and express the value of their client according to what each prospective buyer class should value about the client.

Why would a privately-held business with a projected deal size closer to $50 million than $2 million find it beneficial to hire an investment banker? Your projected deal size increases as your company's prominence (revenues, branding, innovation) increase. With more prominence and a bigger prospective deal, your company is marketable to more types of buyers, strategic and financial, public and private, regional, national, and international, competitors, and other companies in your stream of commerce. As this menu opens up, so does potential purchase price multiple and deal complexity, resulting in a wider choice of deal structure and type and mix of consideration. Also, as the size grows, frequently, so do the number and classes of stakeholders whose interests need to be resolved to get to the finish line. Working with, indeed exploiting, these elements to maximize your equity value recovery is, in the purview, the stock-in-trade of the investment banker. To not blow the conditions to the exemption permitting it to serve, as buyer-type and deal structure diversify and complexity deepens, the business broker must still walk within the lane defined by the enabling exemption to get a deal done and, in the case of the tail wagging the dog, might need to preclude the client from exercising certain choices to continue to serve the client for compensation.

What might other differences between business brokers and investment bankers bear on your decision? Generally, there are three: Reliability of Competency Certification, Regulatory Oversight, and Ease of Due Diligence on Bankers' or Brokers' Relevant Past Business Conduct and Sales Practices.

Competency Certification. Investment bankers must pass a general competency test, a Series 7 General Representatives Examination, or a Securities Industry Essentials exam, and a Series 79 Investment Banking Representative Examination. Series 79 measures the degree to which each candidate possesses the knowledge needed to perform critical investment banking functions, including advising on or facilitating debt or equity securities offerings through private placement or public offerings and mergers and acquisitions. Generally, to manage other bankers on client engagements, bankers must take the Series 24 General Securities Principal Exam. FINRA constructs, administers, oversees, logs, and publicly reports successful attainment. FINRA also mandates and supervises the scope of annual continuing education in two elements, a regulatory element authored by FINRA covering all pertinent regulations and a firm element designed by employing firms to cover their principal areas of activity. At a more granular level, a firm's Written Supervisory Procedures (WSPs) govern the scope and methods of investment bankers' business activities. FINRA oversees the content and coverage of a firm's WSPs and audits for individual professionals' compliance at regular and irregular intervals.

There is nothing equivalent for business brokers. Thirty-nine states have no regulatory gating criteria for business brokers. States like California require that the principal of a business brokerage firm obtain a real estate broker's license. There is, at most, a tangential intersection between a business broker's activities and that of a real estate broker. Generally, real estate is a sideshow in the sale of a business. In California, a business broker's continuing education requirement consists of 48 hours over four years, divided among primarily consumer protection, consumer service, and ethics. There are "certifications" created by the business brokers themselves, banding together to establish self-determined criteria to distinguish members for marketing and branding purposes. These include such as "Merger and Acquisition Master Intermediary" ("M&MAI"), "Certified Business Broker" ("CBB"), and "Certified Business Intermediary" ("CBI"). M&MAI certification requires a business broker to document three years of "M&A experience" in the last ten years, be CBI-certified and take additional courses from the M&MAI certification sponsor, M&A Source™. Additionally, the business broker must have attended two M&A Source™ conferences and completed three deals with sales prices over $1.5 million. To remain active, certified members must attend association conferences. To earn and maintain a CBI certification, in addition to signing up for the association membership agreement, the aspirant must facilitate five California-based "business opportunity" transactions within the last four years, of which three were seller representations. The closed transactions must have minimum gross transaction proceeds of $100,000 or a minimum gross success fee of $10,000. (Investment bankers also have associations that issue certifications, but the audience for these are within the securities industry, like "Certified Compliance Professional." They are not constructs intended to distinguish firms and bankers to prospective clients.)

Regulatory Oversight. Investment bankers, and their firms, are enveloped by regulations from centralized authorities governing procedures and behaviors under constant surveillance and testing (audits) at scheduled and unscheduled intervals as bankers and firms travel through space and time, from industry entry to retirement. Federal, national, and state authorities, regional stock exchanges, and the SIPC regulate investment bankers and their firms. The SEC sets the overarching regulatory scheme, and FINRA makes the daily, weekly, monthly, and annual regulation of firm and individual banker activities. FINRA administrates required competency testing and frequent mandatory continuing education. At an even more granular level, each firm's Written Supervisory Procedures ("WSPs") guide the business activities and conduct of the firm and each banker in every role. The regulators also review the WSPs and individual banker compliance. For investment bankers and their firms, the regulatory environment is like surveillance by an omnipresent constellation of satellites and sensors recording, cataloging, and reporting on virtually all aspects of the firm's and the banker's business conduct with the outside world.

So long as a business broker does not violate the conditions for maintaining its exemption, federal securities regulators ignore them. Thirty-nine of fifty states' regulators ignore them. Among the states that regulate business brokers, the most common method is oversight by the same body overseeing real estate transactions, as in California. However, real estate departments do not interfere much or at all in a business broker's main activity, selling a business. Real estate is often not involved in selling a business. There is no routine or surprise reconnaissance by state regulators and no logging routines to populate public records. Think ad hoc aerial surveillance for business brokers only when a wronged party shoots a flare, bringing fraudulent or incompetent business practices to the attention of law enforcement.

Due Diligence on the Business Conduct of a Business Broker vs. an Investment Banker. It's easy to do first-hand due diligence on investment bankers and their firms, and you can be confident that the information is valid because it is third-party-vetted. It is much more challenging to chase down any reasonably complete vetted record of the professional conduct of a business broker.

For investment bankers, FINRA does most of the work for you. FINRA expends hundreds of thousands of person-hours and millions of dollars yearly on rule-making, surveillance, adjudication, discipline, and tracking systems covering firms and individual bankers. FINRA tracks the firms throughout their history and individuals across firms throughout their careers. Then FINRA rolls up, catalogs, and makes publicly accessible, relevant, and verifiable business conduct data. What information? Business activities permitted, qualifications examinations passed, licenses (registrations) held, employment history in and out of the industry, and very importantly, a running disclosure of customer complaints, registration requirements violations, any convictions, pleas to crimes, investment-related civil injunctions, breach of investment-related statute or regulation, or investment-related civil action, or being named as a defendant in an investment-related, consumer-initiated arbitration or civil litigation alleging a sales practice violation that resulted in an arbitration award or civil judgment. When something serious occurs, or enough bad stuff accumulates, FINRA drums the banker out of the corps, or much worse. FINRA NEVER endorses firms or individuals. Instead, think of FINRA maintaining a review site overwhelmingly skewed to detect negative information. It's scored like golf; the fewer strokes relative to time on the job, the better. How do you access this trove of data to do due diligence for an investment banker and firm? Check the background of any firm AND the investment banker pitching you at BrokerCheck™ and Finra Disciplinary Actions Online™.

For business brokers, it's more challenging to get verified useful information. Federal regulators do not mess with business brokers if they stay in their lane. Thirty-nine of fifty states do not require any form of license to be a business broker. Among the minority eleven, California is typical. California regulates its business brokers through its Department of Real Estate. State real estate departments and licensing boards do not continually, actively, and invasively surveil broker business conduct and sales practices. In California, business brokers come under the California Business and Professions Code section entitled: "Real Estate, Subdivided Lands Law and Vacation Ownership and Timeshare Act of 2004, as amended and in effect January 1, 2020. This rule set captures sales of a business by including among its regulated transactions like the purchase and sale of houses, condos, and apartment and office buildings, the purchase and sale of a "Business Opportunity" (Section 10030). Allegations of bad conduct selling a business are not always plug-compatible with a rule system governing activities and conduct of selling real property for consumers. Although the California Department of Real Estate License Check database License Look-up does provide a field for disciplinary incidents, it requires the ad hoc initiative of a wronged party to submit, file, and follow through. A longitudinal comprehensive professional background check on a single business broker or firm is impossible because of the inconsistency and dispersion of measurements and the systemic friction to data collection. The database exists, but relative to the validity and comprehension of the databases tracking investment banker business and sales practices conduct, it exalts form over substance.

Summary and Conclusion

As the projected value increases for your proposed private company sale, your addressable market of prospective buyers grows by volume, type, and geography to include public companies and financial (passive) buyers, often out of your region. The likelihood of receiving more complexly structured offers, including non-cash (securities) elements, also increases. More prominent private companies may need to accommodate more stakeholders by number and class by increasing the complexity of the deal structure. A registered investment banker can handle, has a professional toolset, and thrives on exploiting the possibilities in this more complex deal space. A business broker is not permitted the same toolset. Operating in the more challenging and potentially more rewarding deal environment with the same or equivalent methods exploited by investment bankers violates the limiting conditions under which federal regulators allow business brokers to provide service.

Still, there is no reason a business broker cannot do a deal for a company closely held by one family, who only want to sell for cash at a number well more than $10 million. Further, as a three-decade personal observation, some business brokers I have experienced are among the most competent professionals to prepare a company internally, under the hood, for sale. They know what to fix and how things need to look. They are frequently better than most accountants at this because the latter operate against a regulated standard (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP), certainly a minimum essential requirement. However, assuming that standard has been met, the business brokers' North Star is the more effective for sale, the wish list of prospective buyers.

I also have observed that a good business broker is usually adept at selling a client to a competitor. The competitor-buyer already understands and shares the target company's principle criteria of evaluation. The corollary is the financial buyer that evaluates an acquisition relative to industry benchmarks, similar to a competitor, often to make the client company a bolt-on to an existing portfolio company in the same industry.

We would expect an investment banker to be better at creating a value story appealing to other classes of strategic buyers, that is, other operating companies, not competitors to the client, but somewhat further afield in function and geography. The prospective buyer, more dissimilar to the client company than a direct competitor, gets more leverage from the client company's capabilities and, therefore, can use a pricing model that reflects the more significant contribution. When you read about the deals done at very high purchase price multiples, they typically were not achieved by selling to competitors racing alongside the client in the stream of commerce who value the client only for its incremental economic contribution. Instead, these deals were done with buyers ahead, behind, and adjacent to the client in the stream of commerce, to whom the seller brought the most of what the buyer did not already possess.

What Does It All Mean for You?

If you think your company will sell for more than $25 million because of its: 1 - financial operating parameters such as revenues, gross margin, EBITDA, and their growth rate, 2 – stylishly in-vogue business model, 3- share of your market in your region of operation, 4- the strength of brand identity, mainly if you sell directly to consumers, 5- novelty and economic leverage from innovation that you control, or – 6 some durable competitive advantage, you are likely to be able to address a relatively wide array of prospective buyers by type (meaning economic role in the stream of commerce), form of business entity and geographical dispersion. The increase in addressable demand will open the possibility of larger purchase price multiples than you have previously considered because you will bring more value to some buyers than others. [To better understand the economic significance of this to you, see my course: "Who Will Buy My Business?" It correlates buyers by type with the willingness to pay higher or lower prices.] As a more comprehensive array of prospective buyers compete to win your acquisition, the door opens to more complexly structured offers, for example, using securities. You may ultimately only want cash but working with mixed consideration offers to get the price up lays the foundation for the negotiations to convert back to an all-cash offer at a higher price than initially proposed. There are other scenarios, but the general idea is that as your marketability increases, you enter the bigger, more complex, and often the more rewarding deal environment that is the preserve of the investment banker with the skill sets and regulated authority to function. Business brokers can get excellent results using more straightforward tools in a simpler market context. Suppose your financial operating parameters, market share, brand identity, innovation, and competitive position, are unlikely to attract attention from a wide array of purchasers by number and type. In that case, a business broker will likely be your better choice. And suppose, for any good reason, you anticipate your purchase price likely to be less than $25 million. In that case, as a practical matter, a business broker will be your answer by default. The projected fee yield of less than $25 million will make it challenging to attract the interest of an investment banker to do your deal. The investment banker's overhead cost and the regulatory burden that qualify them to serve you well on a larger field of play do not decrease with deal size.

Below is a table that summarizes the main differences from a prominent private company's point of view of the significant differences in regulatory requirements and oversight between business brokers and investment bankers.

Stay connected. We won't waste your time. We'll only communicate when we have something to say you are likely to find useful.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.